Coastal environments are subject to multiple interaction. This includes, the marine environment, the terrestrial environment, the atmosphere, biospshere, fluvial systems and tectonic processes; not to mention human development and management. This fascinating interaction all takes place within a tiny strip of land/sea interface that we call the coast. Each coast is unique to its own place and each is unique to its own set of interaction. Getting to grips with these different interactions is challenging but with the right framework of geographical thinking it’s possible to develop a real understanding for how coasts appear the way they do and for how these multiple processes combine to constantly change them.

The basics…

The three principle marine processes that influence coasts are erosion, transportation and deposition. Erosion refers to the breaking down of the land by the force of waves. Transportation is the work of waves and tides in transferring this broken material somewhere else and deposition refers to the process by which waves and tides lose energy, cease to transport and release eroded material. Each coastline has its own balance and equilibrium of erosion, transportation and deposition, which is heavily influenced by a vast numbers of interactions referred to in brief above. As reult we can coin the phrase coastline of erosion or coastline of deposition.A good summary of these processes and interactions is presented in the folowing vido clip from the government’s Environmental Agency in the UK

The four ways that waves and tides erode the coast are described below:

- Hydraulic action. Air becomes trapped in joints and cracks in the cliff face. When a wave breaks, the trapped air is compressed which weakens the cliff and causes erosion.

- Abrasion. Bits of rock and sand in waves are flung against the cliff face. Over time they grind down cliff surfaces like sandpaper.

- Attrition. Waves smash rocks and pebbles on the shore into each other, and they break and become smaller and smoother.

- Solution. Weake acids contained in sea water will dissolve some types of rock such as chalk or limestone.

There are four ways that waves and tidal currents transport material:

- Solution. Minerals are dissolved in sea water and carried in solution. The load is not visible. Load can come from cliffs made from chalk or limestone, and calcium carbonate is carried along in solution.

- Suspension. Small particles are carried in water, eg silts and clays, which can make the water look cloudy. Currents pick up large amounts of sediment in suspension during a storm, when strong winds generate high energy waves.

- Saltation. Load is bounced along the sea bed, eg small pieces of shingle or large sand grains. Currents cannot keep the larger and heavier sediment afloat for long periods.

- Traction. Pebbles and larger sediment are rolled along the sea bed.

Sediment Cells

The processes of erosion, transportation and deposition within the coastal margin is largely contained within sediment cells or littoral cells. There is thought to be 11 large sediment cells in England and Wales as shown in the map. A sediment cell is generally thought to be a closed system, which suggests that no sediment is transferred from one cell to another. The boundaries of sediment cells are determined by the topography and shape of the coastline. Large features, like the peninsulas, such as the Llyn Peninsula in Wales act as huge natural barriers that prevent the transfer of sediment. In reality however, it is unlikely that sediment cells are fully closed. with variations in wind direction, and tidal currents. it is inevitable that some sediment is transferred between cells. There are also many sub-cells of a smaller scale existing within the major cells.

Rate of Erosion

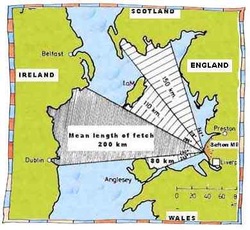

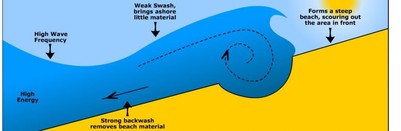

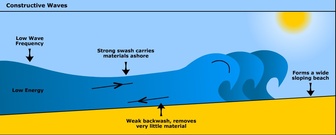

Rates of erosion vary from place to place depending on many factors. An important factor to consider is the type of wave and the distance a wave has travelled. Fetch describes the length of time and space that a wave has travelled. The larger the fetch the more time wind has had to act on waves, hence the larger the wave. Large oceans with large fetch produce large waves, called destructive waves. These waves have large wave height and short wave length and are characterised by tall breakers that have high downward force and a strong backwash. They have high frequency, between 13 and 15 waves per minute. This downward energy helps erode cliifs. In addition, due to a dominant backwash they erode the beach making for narrow steep beach profiles. Localised storms with high wind speed also form destructive waves as well as steep depth gradients around headlands. Small oceans with small fetch develop constructive waves. Constructive waves have low wave height and long wave length with low frequency, between 6 and 8 waves per minute. Constructive waves are associated with weak backwash and strong swash, which builds up wide flat beaches and so amore associated with coasts of deposition. Size of fetch and type of wave are really important factors influencing rates of erosion.

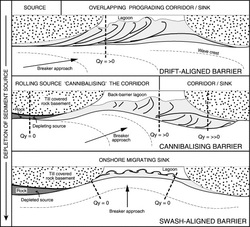

Coastal Topography

The shape of the coastline and its orientation to oncoming waves is also an important factor to consider. An area of coastline may be generally influenced by a large ocean fetch but because of its orientation it may be sheltered from destructive waves. In small bodies of ocean or coastlines that are protected by offshore barriers or islands, prevailing wind is unable to influence wind direction and so waves approach the coast parallel to the shore. In this case coasts are said to be swash aligned. Swash aligned beaches build up large beaches with possible dunes that offer protection from erosiont. For coastlines exposed to large open ocean, prevailing wind dominates wind driection and waves approach the coast at an angle. These coasts are said to be drift aligned and associated with long shore transportation of sediment. Generally these coasts have narrower beaches and may, depending on geology, be exposed to higher rates of erosion.

Geology rock strata

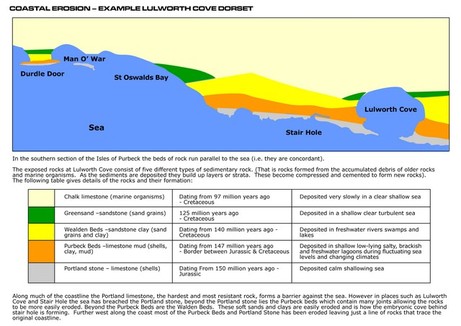

The geology of the cliff is a really important factor that influences the rates of erosion. The resistance of rock essentially determines differential rates of erosion. As we can see in Swanage, along the (very beautiful) Dorset coast. Two headlands, Ballard Point (chalk) and Durlston Head (limestone) of harder rock types are more resistent to erosion. As reult they jut out to sea, forming headlands. The softer clays of swanage have eroded much faster to form the bay. Coastlines, where the geology alternates between strata (or bands) of hard rock and soft rock are called discordant coastlines. A concordant coastline diminated by limestone in the map has the same type of rock along its length. Concordant coastlines tend to have fewer bays and headlands. A close up of Lulworth Cove in the map below shows that bays and coves can form at concordant coasts, once gaps in the resistent rock become breached. In this case, the Portland limestone has been breached at several points. Once broken through, the sandstone clay can be easily eroded to form a cove.

Headlands and bays don’t always form due to alternating strata. In some cases, along concordant coasts they form as a result of a line of weakness, such as a fault or a particuarly well-jointed section of cliff; or as mentioned earlier as a result of its exposure.

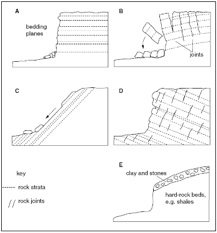

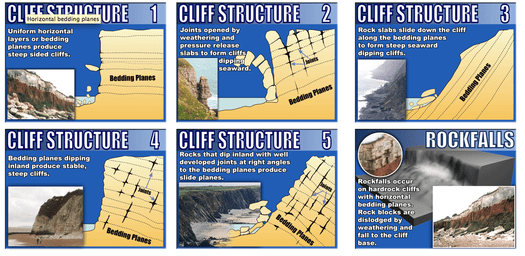

Geology – Cliff Profiles and Bedding Planes

The cliff profile will have a significant impact on the rates of erosion. Sedimentary rocks form as layers of deposited sediment, either on the beds of ancient oceans or rivers. Bedding planes layers of sediment that represent surfaces of exposure that occurred between depositional events. If the bedding planes are horizontal (A) then the cliff profile will be stable with a steep cliff face. However, due to tectonic movement, rock is uplifted and folded. This can change the alignment of strata in cliff profiles. Rock that has been lifted with its bedding planes tilted downwards away from the coast (D) create very stable cliff profiles. Rates of erosion will be slow as the cliff is supported by deeper running strata. Conversely, bedding planes that tilt upwards (C) have a cliff profile similar to the angle of tilt. This is due to the frequent mass movements that occur when the base of the cliff is eroded by wave action. Other profiles, like (B) can be very vulnerable to erosion. In this case the bedding planes are tilted away creating a gravitational pull on the rock. In addition severe joints formed by weathering further speed the rates of collapse. These processes are suberbly animated below.

Sub-Aerial Processes

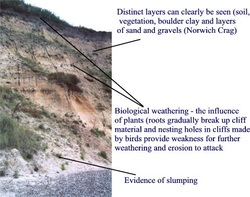

The rate of erosion of coasts is also assisted by sub-aerial processes. Sub-aerial processes refer to the processes of weathering and mass movement. Weathering is the breaking down of rock in situ. It can be divided into mechanical and chemical weathering. Mechanical weathering refers to physical processes like freeze-thaw action and biological weathering. Freeze-thaw weathering breaks up rock as water freezes in cracks. The ice applies pressure and breaks the rock. Biological weathering is caused by the roots of vegetation and nesting birds. A more common type of mechanical weathering found at coasts is salt chrystalization. This occurs as waves deposit salt chrystals in cracks and over time the salt like ice applies pressure to the crack. Chemical weathering occurs as a result of a weak chemical reaction between water and rock. eg. with limestone. Carbonic acid, formed from rainwater and carbon dioxide, will react with calcium carbonate in limestone to form calcium bicarbonate. Since calcium bicarbonate is soluble in water, the limestone effectively gets weathered when carbonation occurs. The role of weathering is to weaken cliffs. This weakening speeds up the rates of erosion. Another sub-aerial process is mass movement. A mass movement refers to the movement of material downslope under the influence of gravity. They can be rapid events, such as landslides and rockfalls or they can be slow processes, such as soil creep. A common type of mass movement at coasts are rotational slumps. Slumps occur due to a combination of factors. Marine processes erode and undermine the base of the cliff. This removes the support of the cliff. In addition rainfall infiltrates into the slope through unconsolidated porous material and then creates a slip plane as it reaches an impermeable material, such as clay. The clay and accumulating water enables the weighted saturated material above to slump. This process can be seen in the diagram below.

Tides

Tides are caused by the gravitational pull of the moon and to a lesser extent the sun. Tides are an important factor in considering coastal processes, as their interaction with the coastal environment to a large extent determines the location of many coastal landforms. Weak tidal currents and a small tidal range will determine the shape and extent of river deltas as well as the size of beach profiles. The extent of the tidal range will also influence the rates of erosion found at cliffs. There are two important tides to take note of; the Spring tide and Neap tide. The Spring tide forms twice in the lunar cycle and increases the tidal range by heightening the high tide mark and lowering the low tide mark. This is caused by the alignment of the moon and sun, which aligns their gravitional pull. The Neap tide produces a low tidal range, in that the higher tide is lower than normal and low tide higher. This again occurs twice in the lunar cycle as a result of the sun and moon acting against each other.

Coastal Hazards

How do scientists keep track of changes in sea level in the U.S.? NOAA’s Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services maintains the National Water Level Observation Network which includes 210 continuously operating water level stations throughout the U.S. and its territories. The first stations started collecting data in the 1850s. Historical data is used to compute relative local mean sea level trends and to understand the patterns of high tide events.

Harmful algal blooms, or HABs, occur when colonies of algae—simple plants that live in the sea and freshwater—grow out of control while producing toxic or harmful effects on people, fish, shellfish, marine mammals, and birds. HABs have been reported in every U.S. coastal state, and their occurrence may be on the rise. HABs are a national concern because they affect not only the health of people and marine ecosystems, but also the ‘health’ of local and regional economies.

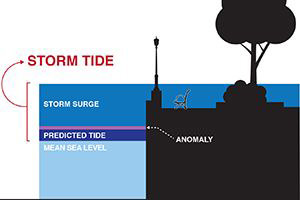

Powerful winds aren’t the only deadly force during a hurricane. The greatest threat to life actually comes from the water—in the form of storm surge. Storm surge is the abnormal rise in seawater level during a storm, measured as the height of the water above the normal predicted astronomical tide. The surge is caused primarily by a storm’s winds pushing water onshore. Storm tide is the total observed seawater level during a storm, which is the combination of storm surge and normal high tide.

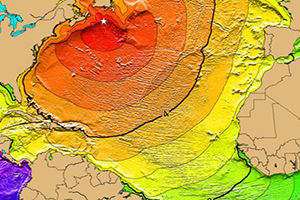

NOS’ primary role in tsunami warning is to provide real-time coastal water level data to NOAA’s Tsunami Program and the public, which is critical to issuing warnings and forecasts during an event. High-frequency water level information is also important to tsunami modeling, both during and after an event, to refine the forecasts as the event progresses, and to better understand tsunami science for future improvements to the National Tsunami Warning System.